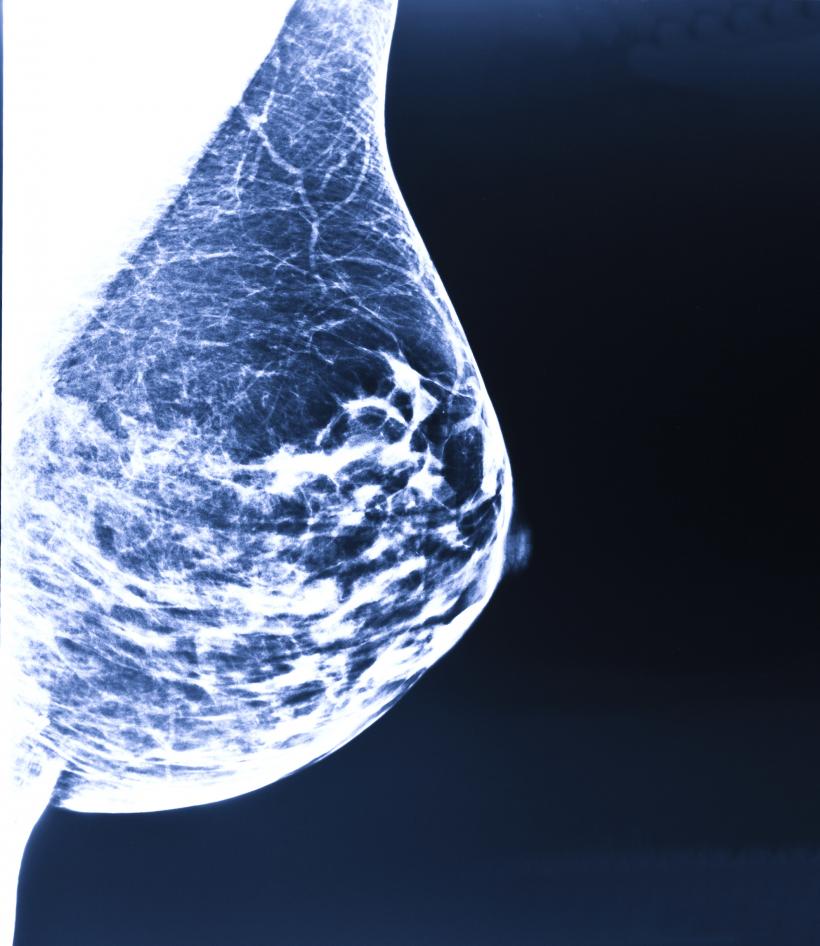

Thinkstock

A new study from MIT is heralding new research that brings us one step closer to forcing a long-time enemy to wave that tell-tale white flag high above its loathsome head.

It's tricky to nail down exactly when we "formally" began battling cancer, but many point to the Nixon administration's "War on Cancer"—declared in 1971—as the pivotal turning point in modern science's now decades-long battle being waged over untimely death. But just in case you want to go all conspiratorial on our asses—It's the hormone-filled milk! It's cell-phone usage! It's microwaves, chronic depression and GMOs!—note that there are eight documented cases of breast cancer that have been found on Egyptian papyrus dating all the way back to 3,000 A.D.

Anyway.

Scientists hailing from MIT (Yarden Katz, Christopher Burge and Rudolf Jaenisch) and China Argricultural University (Feifei Li and Zhengquan Yu) have made an exciting discovery. Prior to their pending paper (which appeared in eLife yesterday), biologists believed that a certain kind of protein—transcription factors (which basically turn certain genes "on and off")—were responsible for the regulation or proliferation of cancer. Meaning, they were the bastards that forced cells into creating more and more sickened cells.

What these eggheads have discovered, however, is that there is an additional protein that could be helping to run this cancer-racket. While it may sound like delectable sushi, Musashi proteins are being implicated as another culprit in the regulation of cancer, particularly in a subset of breast cancer.

Musashi proteins are RNA-binding proteins, which are responsible for a host of crucial cellular activities including cellular function, transport and localization. "Human cells have about 500 different RNA-binding proteins, which influence gene expression by regulating messenger RNA, the molecule that carries DNA’s instructions to the rest of the cell," explains the MIT News Office.

Prior to this study, very little had been learned about the specific functions of Musashi proteins—previously these RNA-binding proteins were used to identify neural stems, "but they also get turned on in cancers," mused Yarden Katz. "That was intriguing to us because it suggested they might impose a more undifferentiated state on cancer cells.” Meaning, the Musashi proteins could perhaps induce cancer cells to transition to a state where they stopped multiplying at such a rapid rate.

In order to suss out his theory, Katz manipulated the levels of Musashi proteins in neural stem cells and then measured the effects on other genes. Katz discovered that those genes affected by Musashi proteins were related to a process known as EMT (epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition), which causes cells to "lose their ability to stick together and begin invading other cells."

Musashi proteins have been proven to be the most highly expressed in a type of breast cancer known as luminal B tumor; it's not metatastic (able to spread from one area to another) but it is aggressive and fast-growing. As the EMT process is known to be an insidious element in breast cancer—it's believed to cause cellular dysfunction, progression and invasion—Katz decided to "knock down" Musashi proteins in breast cancer cells grown in the lab.

And, Eureka!

The breast cancer cells were forced out of their "epithethial"—or stable—state. Conversely, when the proteins were boosted with mesenchyma cells (which have a high ability to differentiate, i.e., become a different kind of cell) the cells transitioned to an epithelial state.

"These proteins seem to really be regulating this cell-state transition, which we know from other studies is very important, especially in breast cancer,” Katz says.

The scientists explain that the next hurtle is to figure out exactly how these Musashi proteins—which typically are turned off after embryonic development—get turned back on in cancer cells. Katz also explains that while Musashi proteins could make good targets for cancer drugs, before we throw ourselves a big ol' hot pink ticker tape parade . . . we have to understand that this particular research is really more about diagnoses than treatment.

But I can already see cancer shaking in its boots . . .